BLACK COMEDY

By Michael G. Glab

© 2013

◆

◆

— Thirty-seven —

Now Tree and Al are grandparents. Try as she might, Tree cannot continue to pretend (outwardly) her daughter doesn’t exist. She (Tree) tells herself this new detente is the right thing: Anna is now a mother herself, deserving of respect and honor. No longer is she the putain college brat who started all these troubles. So Tree is this close to fully re-embracing Anna, except for the presence of that goddamned Anthony Pontone she’s married to.

Tree has gone so far as to give Al her blessing to visit Anna every evening to bring her bags of groceries, formula, and more than enough money to pay the utilities. Now and again, Tree makes a nice lasagna and wraps a titanic slab in tin foil for Anna’s care package. With all the twenties and fifties Al is slipping into her hand, Anna now has enough money that Anthony can stop by occasionally and take what he needs, for he has to eat too. Anthony times his visits to coincide with Anna’s sleeping schedule. She knows he pockets a twenty every time he swoops in but she doesn’t protest — besides, who’s she going to protest to? Anna makes no effort to hide her little stash of money. Even though he is a fucker, Anthony still is her husband and Anna doesn’t want him to starve. To get run over by a garbage truck? Maybe. But not to starve.

Neither Anthony nor Anna can remember the last time she called him Mr. Brown.

◆

July and August. Astronauts land on the moon. Chappaquiddick. The ritual and gruesome murders of a half dozen people in the Benedict Canyon neighborhood just north of Beverly Hills. Woodstock. The greater world swirls. Anna’s stagnates. The novelty of raising a child with absolutely no help from her husband has worn thin. No help with the diapers, the midnight feedings, the rockings to sleep, the bills, but, Anna concludes, perhaps the worst thing is the solitude. Oh sure, for the first few months, the little eating and poo-ing machine was all the human company Anna needed but now, with him reaching the advanced age of one year and able to keep himself occupied by batting at the multi-colored mobiles hanging over his crib and jamming everything in the world into his mouth, Anna has at least a couple of hours a day during which she can brood about the state of her marriage.

For most of the first year of his son’s life, Anthony spentg as little time as possible at home for a variety of reasons, the most immediate two being the dirty looks Al and Tree shot at him every time they caught sight of him and the shit-eating grin Sal Sanfillipo wore whenever he saw the commie fag hippie neighbor he’d clubbed into dreamland twice — or was it three times? — the year before.

And the result of all the planning and hard work he and his cohorts had done to get a hundred thousand protesters in Chicago to flip the bird to the Party of Death? Well, only a tenth of them showed up after all, but man, they made the Whole World Watch. And — right on, man! — the Party of Death was evicted from the White House.

Only the new occupant is one Richard Milhouse Nixon. In the first six months of 1969 — the first six months of the new Nixon administration — some 4500 U.S. soldiers have been killed in Vietnam. In June, Life magazine runs photos of 241 American soldiers killed in action in a typical recent week. The magazine-reading public is aghast. Vietnam becomes not Lyndon Johnson’s war nor Bob McNamara’s war, but Richard Nixon’s war.

By the Fall, Anthony is enraged not just by the war but by something else, something, he is not quite yet prepared to understand, more personal. Nixon’s Attorney General, John Mitchell, in March had pushed a federal grand jury to indict eight men for planning the Convention riots. Anthony wonders why he wasn’t indicted too; damn it, he’d worked harder than any of them. But Abbie and Jerry are big. As are Rennie Davis and Bobby Seale, Dave Dellinger and Tom Hayden. And just for good measure, The Man also threw the book at a couple of harmless East Coast intellectuals, Lee Weiner and John Froines. When Anthony reads about the indictments in the Sun-Times, the first thing he says to himself when he comes to the last two names is, Who?

As far as Nixon’s Department of Justice is concerned, Anthony Pontone doesn’t exist even though he chartered buses, participated in negotiations with City Hall for marching permits, helped set up self-defense seminars in Lincoln Park, put out the call for medics and nurses to help with any potential casualties and, for chrissakes, even made sure the 24-hour diner on the first floor of the Lincoln Hotel had put up extra urns of coffee for the kids who were gonna sleep overnight in the park — that is until they were beaten, gassed, and chased out by Mayor Daley’s pigs. Fuck, man.

As for Mayor Daley himself, the last thing in the world he wants is for a Chicagoan to be indicted. No way he wants one of his own lumped in with all those frizzy-haired, pointy-headed outsiders who started all the trouble. Plus, Daley’s no dummy; he makes sure, through his man in Washington, Dan Rostenkowski, that the Justice boys wouldn’t hand in an indictment against the son of the powerful Northwest Side mob boss, Tony The Fist Pontone.

And when Tony The Fist gets wind of the strings Daley had to pull to keep Anthony out of court, he directs Al, Mickey Finnin, and Rocco Bianco to do business with the mayor’s kid, John, the insurance man. John Daley happily draws up policies on all the burned-out shells and vacant lots on the West Side they’ve been snapping up.

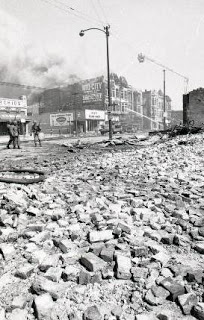

“You sure knew what you were talkin’ about that night,” Mickey says to Tony the Fist of the summit on Al’s back porch as the West Side burned the day after Martin Luther King was killed. “Everybody wins. We get our nice little real estate investments there. Old Man Daley’s kid gets our business. Even the Coloreds get their street named after that Martin Luther. Boyo, like they say, this is the city that works.”

Everybody Wins

■

All Anthony has to show for the enormous amount of work he did in the spring and summer of ‘68 are two permanent lumps on his head. Or is it three? The least The Man could do is file federal charges against him — and put his picture on the front pages of every newspaper in the country. But no, all he gets is dirty looks from Anna parents and that brutal pig Sanfillipo grinning at him.

◆

By the end of the summer of 1969 the rage Anthony feels for this fucked-up, unfair, corrupt, sick world has eaten a hole in his stomach. He must spend more time at home — Ugh, that Pleasant Valley Sunday, square, straight prison with Anna as a bunkmate and the 24-hour din of a squalling baby, how did this all happen to me?

Anthony lays his head down regularly on Natchez Avenue now because he must watch his diet; milk and farina, white bread and peanut butter seem to be the only foods that don’t cause him to double over in pain. Regular sleep keeps the agony at bay as well.

The forced domesticity brings about an unintended consequence. By late September, spending time with that 24-hour a day squalling infant turns out to be, well, not so horrifying after all. “Man,” Anthony tells Anna, “he really doesn’t cry all day long anyway.” In fact, holding little Chet in his arms actually calms Anthony’s roiling stomach.

(Anthony had insisted they call their baby Che, after Fidel’s pal. Anna told him no way but he went ahead and had the nurse fill out the birth certificate with that name anyway. Later, after Anthony had left the hospital, the nurse came in and showed Anna the birth certificate. Together, they came up with the idea of simply adding a T after Che. And so, Chet it was. Naturally, Anthony was deeply offended that the two women had conspired to defy him. When Anna would complain about his absences from home, Anthony would say, “How can I spend time under the same roof with someone who’d do that to me?”)

Che & Fidel

■

That was then. Now, who’d have ever guessed Anthony would find himself falling in love with his baby son?

◆

Anthony has become so fond of the little pistol that he finds it difficult to leave him the morning of Wednesday, October 8th, 1969. But a man has responsibilities, especially a man consumed by rage.

Anthony kisses Chet on the forehead and lays him in his crib. “I’ll see you tonight, little man. Don’t get yourself in any trouble,” Anthony says as he pinches Chet’s big toe. Chet responds with a hiccup and a fart. Anthony chortles.

Anna’s voice comes from the kitchen. “Anthony, are you leaving? Where you going?”

“Out,” Anthony says.

“‘Out,’” Anna repeats aloud. “I’m married to a teenager.”

Anthony doesn’t hear her. He trundles down the stairs and lets the front door slam behind him. He’s on his way downtown. These are the Days of Rage.

To be continued

◆

All fictional characters, descriptions, and situations are the property of the author.

▲